March 02, 2020

Why Not Design-Build?

DESIGN-BUILD VS. DEDICATED ARCHITECTS

Design-build firms garner lots of hype these days, but are they as good as they seem? Reports from homeowners who’ve taken this path of renovation are mixed, with some voicing real regrets. The complaints include sketchy craftsmanship, heavy change orders, stop work orders, and endless delays in job completion. Is this just the bad luck of a few homeowners or a systemic problem?

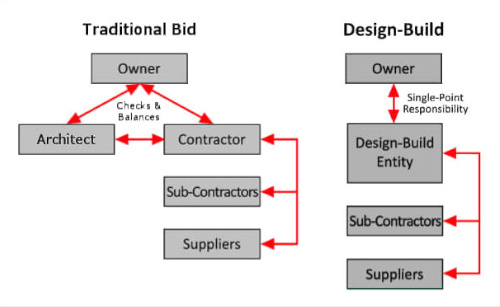

First, let’s clarify the difference between the design-build process and the traditional architect-contractor relationship. Design-build is a streamlined process that offers clients one-stop shopping. A single company provides all the services needed to design, price, and build the project. At first glance, the process seems collaborative, cooperative, quick, and efficient.

By contrast, a traditional dedicated architect works solely for the client and bids out the construction to a competing pool of general contractors. The bidders struggle against conflicting desires to lower prices to win the job and to raise prices for profit. And if bids come back higher than expected, the architect must then redesign to lower the price. Design-build skips all this back and forth by estimating costs during the design process.

MISSED OPPORTUNITY

But we’d argue the back and forth is exactly the reason for sticking with tradition. Competition may seem adversarial, but it’s a fight that benefits the client. A builder will always work harder to lower his prices when he’s vying with other bidders to land a job. By eliminating this struggle, design-build costs the client the single greatest opportunity for savings.

Moreover, design-builders exaggerate the time difference between the methods. A design-builder can’t price a job any faster than competing bidders can. And while it’s true that design-builders get more practice at detailed cost estimating than architects do, any architect with a few years’ experience in a given market can accurately predict construction costs.

In our office, for example, our budget estimates typically fall within 10% of the competitive bids we receive. Here’s why. If an architect has recently bid out six similar projects to four contractors apiece, that’s a data trove of twenty-four detailed bids to use for estimating future projects. A design-builder would need twenty-four separate projects to amass as much data.

DEFEND THE CLIENT

Another traditional benefit for clients is the triangle of checks and balances that links the contractor, the architect, and the client. The dedicated architect is the client’s agent, not the contractor’s. As such, the architect has a fiduciary duty to the client and defends the client against the contractor’s mistakes. Since most clients have little experience with construction, having a seasoned professional on your side can be a crucial advantage, especially if something goes wrong during construction. And construction is rarely a smooth process.

Here’s a common example. A contractor proposed a substitution for our design: he wanted to cover the chimneys in waterproofing, rather than cut stepped flashing into the brick, as we’d spec’ed. Even though this kind of “repair” is common practice, it’s short-sighted. If you let bricks breath, they’ll last a lifetime, but if you wrap them in waterproofing, the mortar corrodes. You’ll have a few leak-free years, but water will eventually get in and turn the mortar to sand. Since we serve only our client’s interest, we vetoed the substitution.

But in a design-build relationship, by contrast, our veto could never have happened. The contractor gets no resistance from the architect because the two are on the same team. No one defends the client. If anything, it’s the opposite. Against a unified front of professionals speaking their own jargon on their own turf, the client is on her own.

Look, we’re great fans of collaboration. We love the synergy of all parties working towards the same goal: making a project the best it can be. And our design and construction process is rarely adversarial. But when it is, don’t you want your architect on your side?