May 21, 2021

Pop-up Hospitals

NYC RECOILS

NYC RECOILS

When New York City became the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, it posed a crushing challenge not only to our front-line medical professionals, but to the spaces they work in. Our overwhelmed healthcare facilities needed instant and widespread augmentation. On March 23, 2020 (a decade ago in corona-time), Governor Andrew Cuomo announced an emergency order that all hospitals in the state up their capacities by 50% to meet the need. But even this steep increase was no match for the surge in COVID-19 patients.

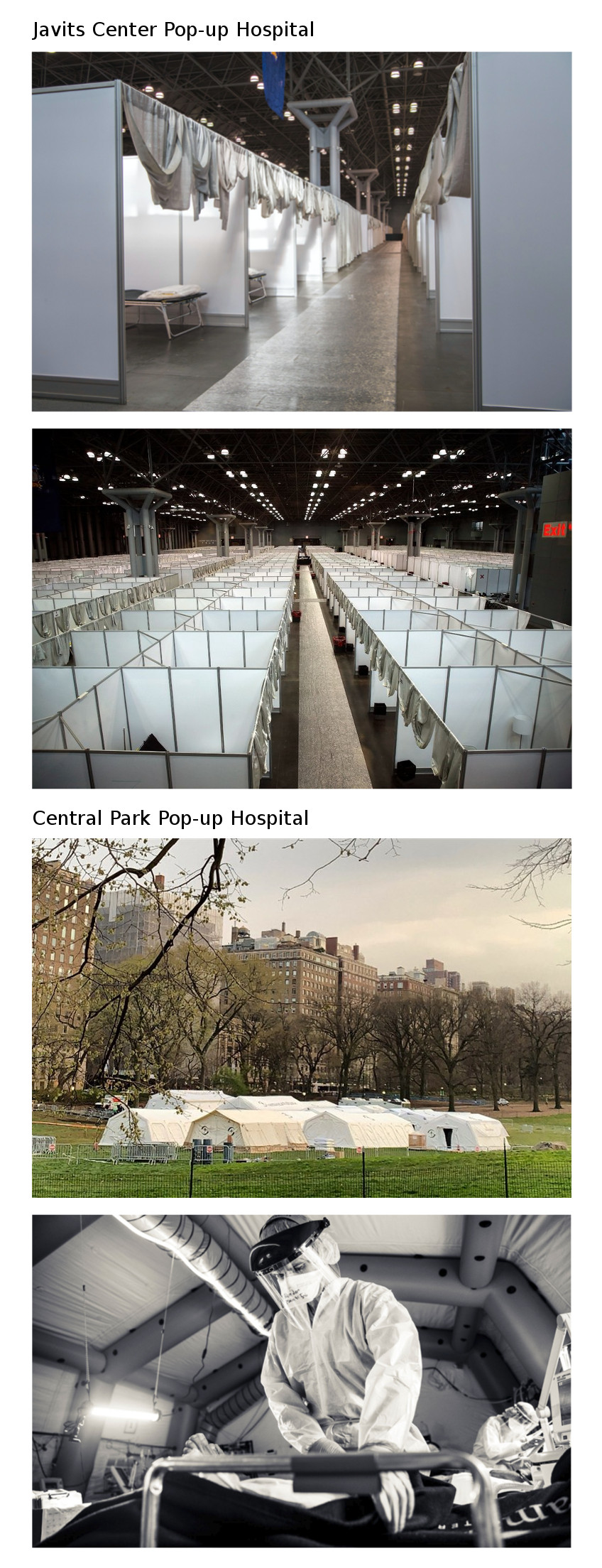

The state raced to build four pop-up hospitals in the middle of the pandemic, some from scratch and others by repurposing existing structures. One was at the Brooklyn Cruise Terminal, another on Staten Island, a third at the Javits Center, and the fourth in the middle of Central Park. We’ll examine the last two as case studies in adaptation. (The federal government’s wrong-footed deployment of the hospital ship USNS Comfort deserves its own blog.)

THE JAVITS MEDICAL CENTER

The Jacob K. Javits Convention Center is one of the biggest and busiest in North America. The transformation of this 1.8 million s.f. building into a massive treatment facility by the Army Corps of Engineers was just spectacular. In less than three weeks, they erected a 2,000-bed field hospital, later expanded to 2,910 beds.

Long, beige curtains screened off row after row of 8-foot-tall cubicles, a quick and effective way of dividing the vast hall into hospital rooms. Most rooms had chairs, oxygen concentrators, and adjustable cots, with additional equipment and PPE devoted to the intensive-care sections. Large restroom trailers were parked inside, like transplants from a music festival.

The place teemed with active duty and reserve military doctors, deployed to New York from all over the country. According to patients, the place looked, felt, and smelled like a hospital, except for one telltale feature–the high ceilings. “When you lie on your back, you remember you’re in a convention center, staring at sky-high ceilings of steel. At night, the lights are dimmed, but they’re never turned off,” one patient reported in April.

Several factors made the Javits Center’s conversion a success. The building was originally designed to adapt to a wide range of events with occupancies in the 10,000 range. Ironically, the virus helped by clearing the Javits’s calendar. What remained was an empty shell surrounding a collection of enormous fully-conditioned spaces. It was the perfect blank canvas for a pop-up hospital.

CENTRAL PARK FIELD HOSPITAL

By contrast, the 68-bed field hospital in Central Park lacked both the benefits and the constraints of a preexisting structure. Erected in the park’s East Meadow, the cluster of 14 tents resembled the set of M*A*S*H, but against a backdrop of Manhattan highrises. Inside each tent was a structural frame of inflatable tubes for compact shipping and quick deployment. A grid of adjustable cots was similar to that of the Javits but without the privacy screens. Ten ICU beds came equipped with ventilators.

Mount Sinai Hospital and Samaritan’s Purse, an evangelical humanitarian organization, partnered to create this facility. But the latter built and ran the site along the lines of field hospitals they’d opened worldwide to address epidemics like the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

Unfortunately, Samaritan’s Purse also has a dark side. The charity is run by Franklin Graham, who has a long trail of homophobic and islamophobic hate speech. When The New York Times exposed Samaritan’s Purse for its policies requiring staff to sign anti-gay pledges and forcing aid recipients to participate in religious activities, City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and other local officials called on Mount Sinai to close the field hospital.

By the end of April, the Central Park facility had treated 315 patients, a drop in the bucket compared with Javits. And the spring timing was lucky; tents would have faced harsher conditions in frigid February or broiling July. But the open ball fields of the East Meadow allowed for adjacencies that best suited the medical staff.

ALL GOOD THINGS…

Earlier this month as the patient crisis ebbed, all of these pop-up hospitals began to wind down. On May 4, the Samaritan’s Purse facility stopped admitting new patients. Their closing coincided with the downturn of COVID-19 cases, but clearly, they were ducking their own backlash. Mt. Sinai plans to take several more weeks to treat the last patients and decontaminate the tents.

The Javits Center closed its admissions on May 1. Only a few dozen patients remain, with releases anticipated shortly as they recover. But the Javits field hospital won’t be broken down yet. FEMA’s equipment will remain since officials expect a second wave of infections. Most of the military personnel who staffed the Javits Center, however, have left New York for redeployment.

These facilities show two extremes of potential site conditions — the conversion of an existing building vs. the creation of a new complex from scratch. But both are laudable examples of a quick and reversible adaptation. An urgent need identified, a swift response mounted, and temporary structures built and occupied in less than a month. This is lighting fast for a city that normally takes months to approve a DOB application. We’re inspired by the quick and thoughtful work of the designers.